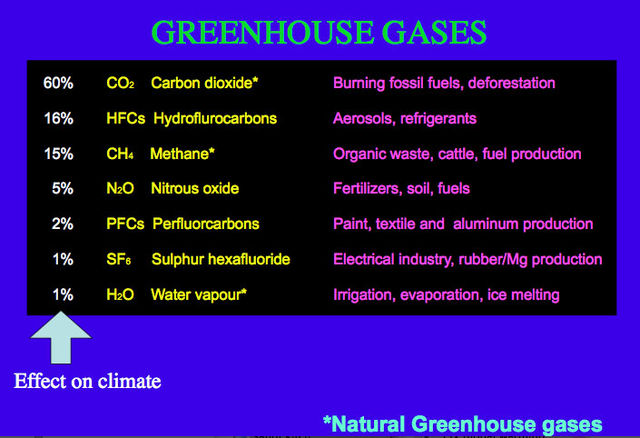

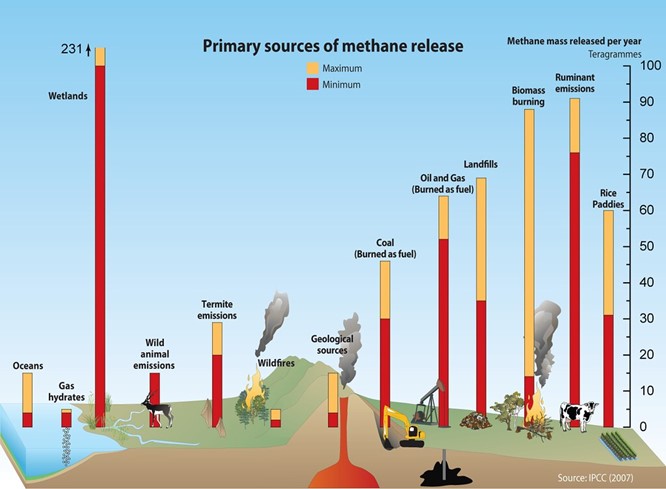

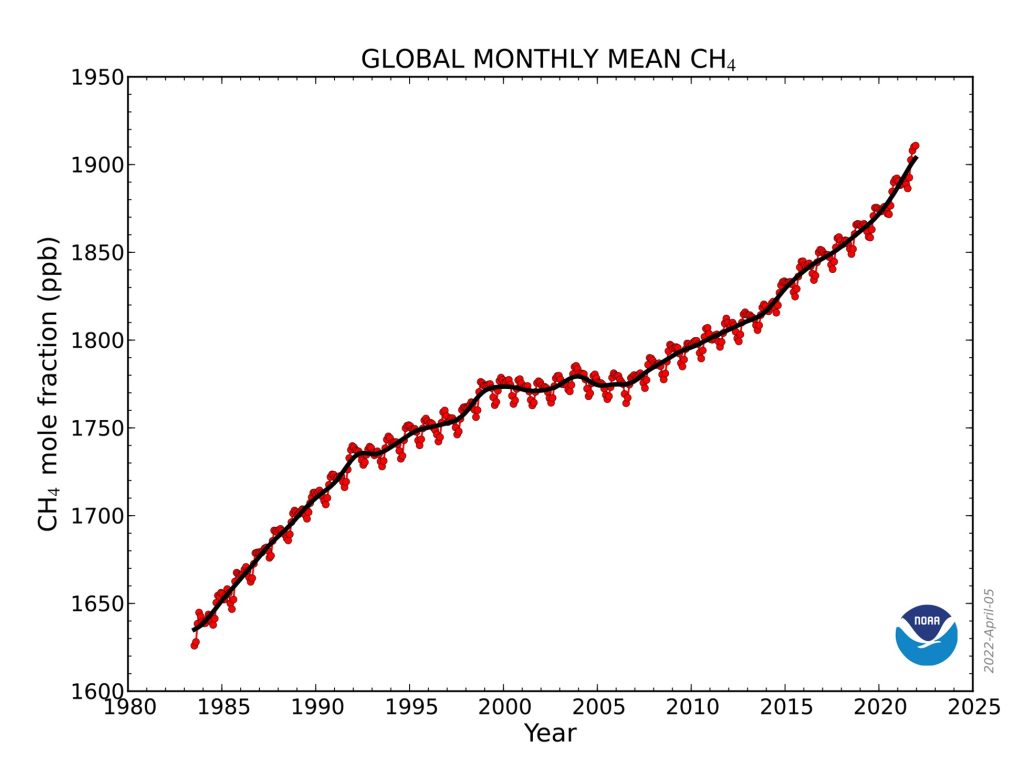

The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is numerically quite low at less than 2 parts per million. However, methane is widely viewed as a potent greenhouse gas because of its global warming potential which is approximately 28 times greater than CO2 on a weight basis. (Some sources claim an even higher multiplier.) Furthermore, atmospheric methane concentration has been increasing in recent years, as seen in the graph below, which is largely attributed to the ever-increasing production and use of natural gas. Other methane sources, including natural ones like swamps and geologic vents, might be larger, but are not growing as fast and are harder to control and mitigate.

According to the US EPA, over half of the methane released to the atmosphere due to the production and use of natural gas originates in the production phase where methane is released, or vented, usually in combination with other produced gases. This venting frequently occurs at smaller, dispersed wells where it is not cost effective to gather and clean the produced gases. Such venting also is frequently associated with wells developed primarily to produce oil where produced gases (also called “associated gas”) are essentially a waste product.

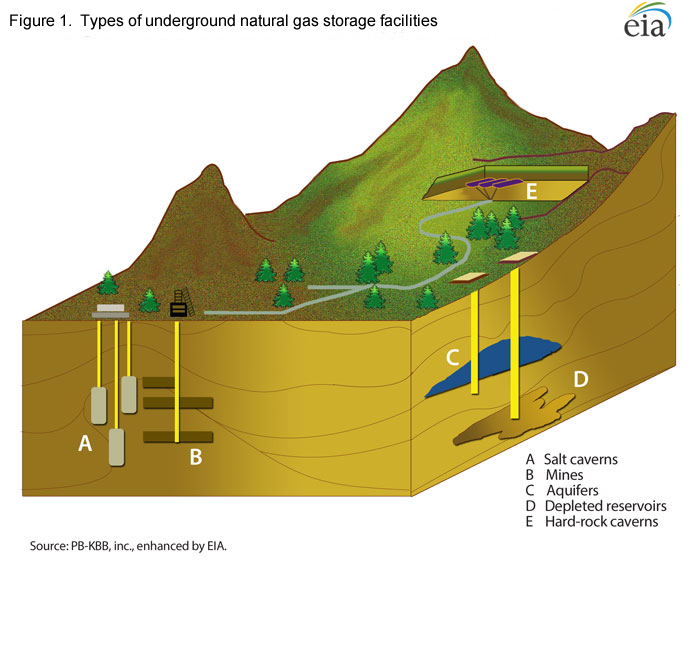

Using an accounting approach different from the EPA, the industry group ONE Future calculates a methane intensity to essentially measure molecules into a pipeline compared to molecules out of a pipeline. The purpose of this approach, as opposed to the more macro approach of the EPA, is to allow individual companies to benchmark and track themselves to promote continuous, publicly accessible improvement. Both distribution and transmission/storage companies using this approach report methane intensity scores of better than 0.1% in recent years (i.e., less than 1% of molecules are “lost” to the atmosphere).

The focus of the pipeline industry is to reduce this loss to an absolute minimum. And to do so, requires zeroing in on all possible sources of these losses.

Methane emissions from pipelines can be generally placed in 3 categories:

The causes, remedies, and environmental rules and regulations for each of these are different.

Fugitive Emissions

These are methane emissions that result from normal, designed-in, pipeline operation. Examples include:

- Minor seepage around compressor rod packing as it wears.

A near-term solution to this release is more frequent maintenance of such wear components. A more permanent solution is new compressor technology, such as hermetically sealed compressors. - On/off operation of pneumatic valves.

We normally think of pneumatically operated devices as running on pressurized air. But more generally, the term “pneumatic” can be applied to any device driven by any pressurized gas. In the case of the pipeline industry, pressurized natural gas is commonly present, so it is logical to use this convenient supply for pneumatic power. Unfortunately, such use necessarily results in the release of methane into the atmosphere as valves are opened and closed. A solution to such releases is replacement of pneumatic valves with electrically driven ones. Note that such substitution can carry the risk of reduced pipeline reliability as the system becomes more dependent on electricity supply. - Microscopic seepage through pipeline walls due to indetectable, small cracks.

All pipes are subject to small leaks, especially as they age. These can be so small that they are impossible to detect, and they can certainly be so small that it is not “cost effective” to repair them (perhaps, unless there are fines or fees). To account for leaks of this type, a so called “emission factor” is commonly used (for example, leaks per mile) based on industry averages. Individual pipeline operators can use detailed surveys of their own particular pipeline systems to apply for lower factors.

Emissions From Incidents

These emissions are due to accidents or equipment failure. The pipeline operator did not intend for these releases to happen and will generally repair as soon as possible, especially since these releases can involve large flow rates of escaping gas. Pipeline operators are always striving to minimize incidents (e.g., “call before you dig” campaigns), so solutions usually are associated with safety and maintenance programs.

Emissions From Venting

Vented releases are those that result from intentional acts by the pipeline operator. Examples include:

- Venting a compressor housing for maintenance or repair

- Opening and closing pigging launchers and receivers

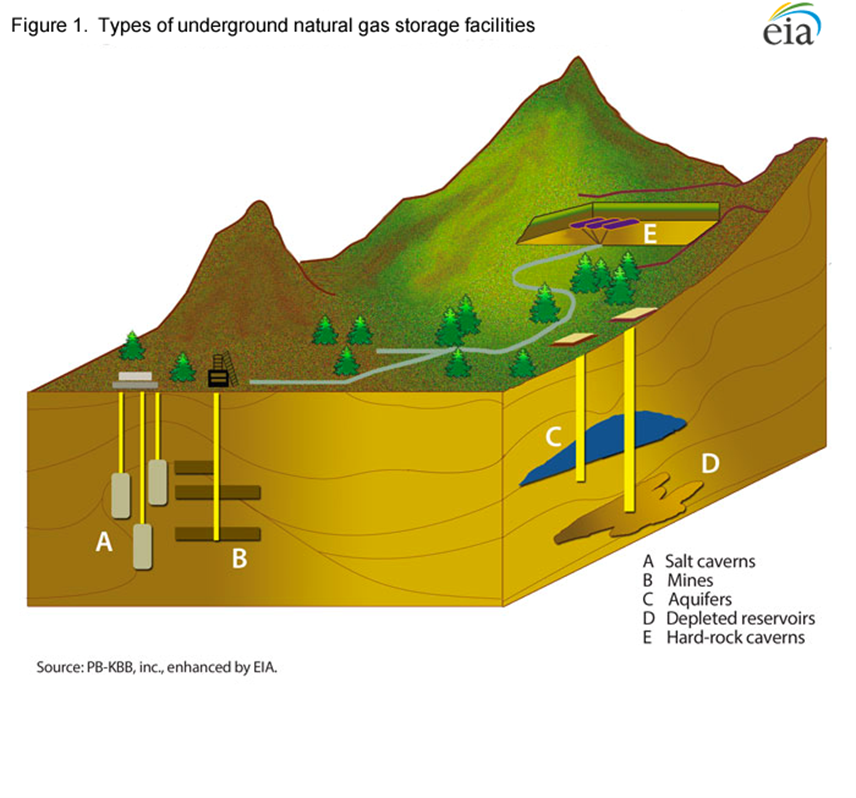

- Blowing down a pipeline for repair, expansion, or decommissioning

Among all types of emissions, vented emissions are the ones that our current GoVAC® products address. These emissions are also the ones that give the greatest “black eye” to operators since they seem to occur by choice and could thus be avoided. Through the products and services provided by Onboard Dynamics and similar companies, the solution to our industry’s “venting” problem is at hand.

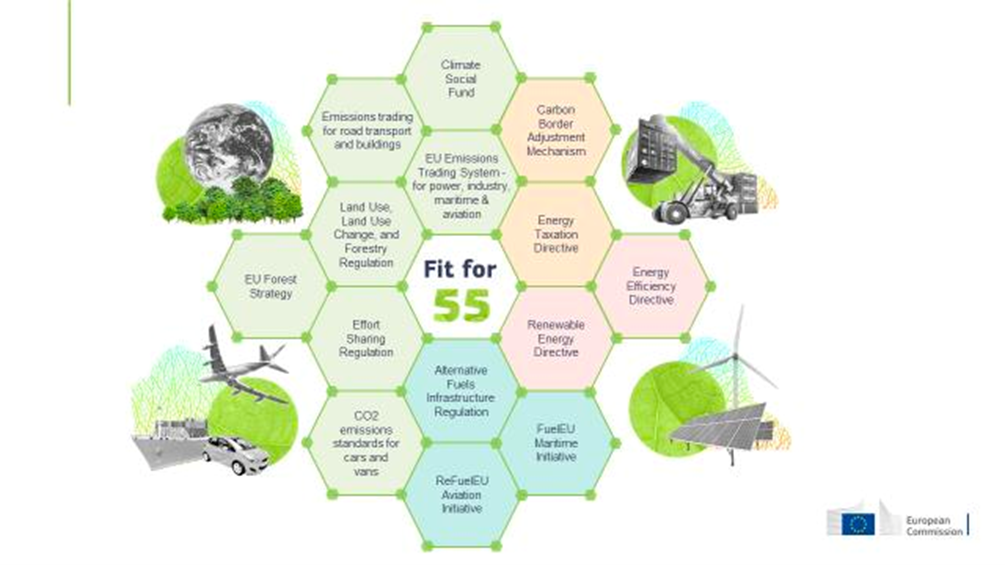

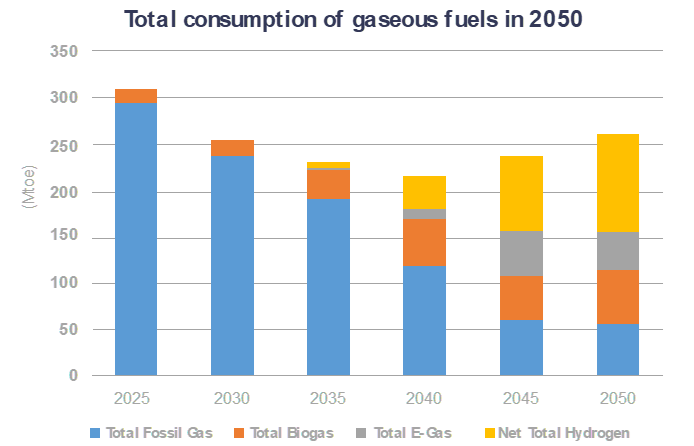

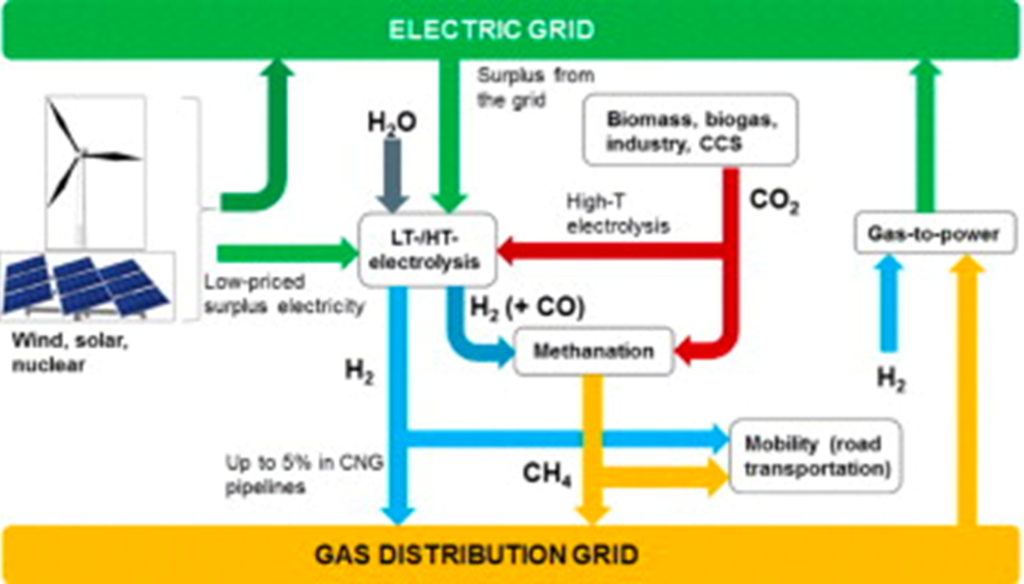

Reducing methane emissions from natural gas pipelines is a significant focus for environmental efforts, as it contributes to climate change. Improved monitoring, maintenance, and the use of new technologies, such as our GoVAC® system, are essential for mitigating these emissions throughout the natural gas supply chain. The natural gas industry will play an important role towards the energy transition as we find long-term solutions to our energy needs.

Jeff is the Technical Advisor/Co-founder of Onboard Dynamics. He is an experienced entrepreneur, having founded or co-founded two companies in the energy and software industries before co-founding Onboard Dynamics.